Dawn Wells

October 18, 1938 – December 30, 2020

Best known for playing Kansas farm girl Mary Ann Summers on TV’s Gilligan’s Island (1964 – 1967)

Farewell, Dawn Wells. Your beauty, sweetness & indefatigable joy in the face of buffoonish seamen, clueless intellectuals & trashy starlets made anyone wielding a Y chromosome fantasize about being cast away with you. You will always be washed ashore in our broken hearts. RIP.

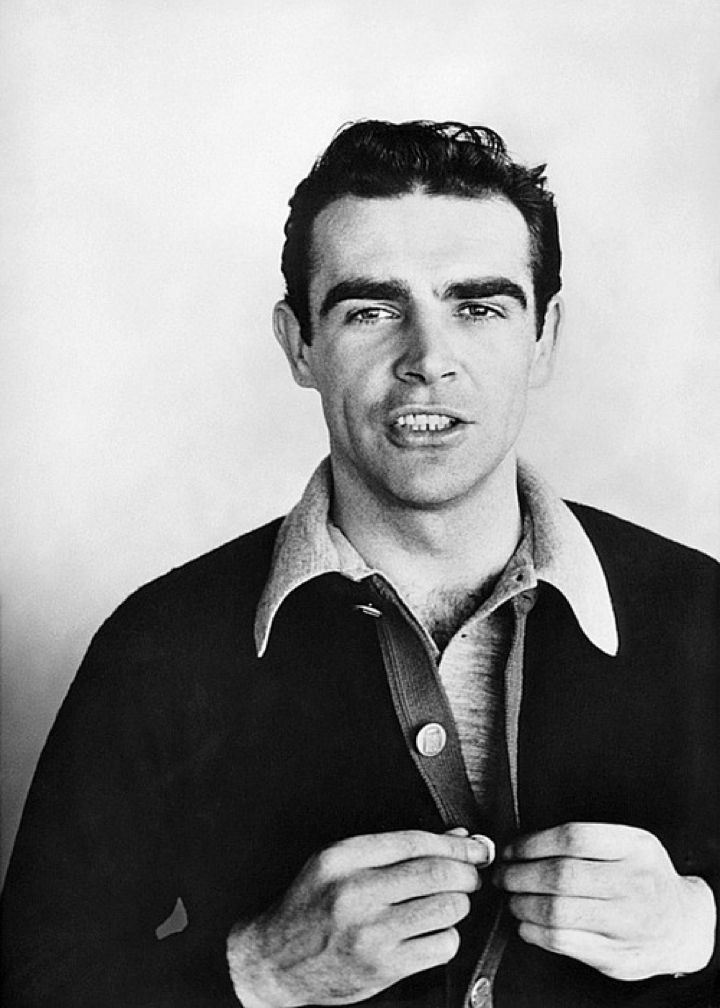

Sir Sean Connery

August 25, 1930 – October 31, 2020

Despite what you have heard by now from fans and critics, Sir Sean Connery was more than just Bond—James Bond. He was more than a rugged Scot in a tuxedo, sipping shaken-not-stirred martinis, who injected Cold War cool and Swingin’ Sixties sexy into the on-screen persona of that debonair superspy with the 00-license to kill. He had more value than that.

Connery excelled at portraying heroes who were not merely “tough guys” who kept nothing more than aggression boiling beneath their skins. He infused his heroes with attributes fools may consider to be effete or even effeminate—charm, wit, grace, intelligence, and warmth. That said, he could switch those off without warning and dispatch a foe without mercy, using a pistol, sword, ejector seat, or even his thumb.

Connery memorably gave life to several outstanding heroes outside Bond’s shadow:

Daniel Dravot in The Man Who Would Be King was a career soldier, mercenary, and rogue, but when fortune inadvertently tagged him as a king of an ancient lost city, he took the role seriously, ruling justly and resolving disputes with diplomacy rather than violence.

In Time Bandits, his King Agamemnon split his time between coolly ordering the executions of his enemies and building a paternal relationship with Kevin, the young time-displaced traveler whom he sought to raise as his son.

Playing Henry Jones, Sr.—the emotionally reserved father of the titular swashbuckling archeologist in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade—he was a scholar, devout Christian, and pacifist who favored non-violent means to thwart enemies (e.g., using an umbrella to harass a flock of seagulls into an incoming Nazi fighter plane)—at least until the Nazi threat proved to be overwhelming.

As nuclear submarine commander Captain Marko Ramius, he eschewed the high-tech weapons at his disposal and relied on his profound military expertise to outmaneuver the deadly enemy tasked with killing him and his crew in The Hunt for Red October.

As explorer and hunter Allan Quartermain, he served as the wise mentor to adult detective Tom Sawyer in (the maligned but eminently enjoyable) The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen.

And in what may be his most beloved role post-Bond, he was incorruptible veteran cop Jimmy Malone in The Untouchables; hard-as-nails to be sure, but savvy enough to understand he needed to take boss Elliot Ness under his wing to help devise the plan to take down gangster Al Capone. For this role, Connery was rewarded with both an Oscar and Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actor.

Connery knew his comfort zone and generally remained within it, but did wander outside for multiple career redefining (he hoped) dramas. Sometimes, like his turn as a thief in The Anderson Tapes, a brutalized POW in The Hill, and an unstable police detective in The Offence, the results were critical, if not always commercial, successes.

But many others, like Hitchcock’s Marnie, A Fine Madness, The Molly Maguires, Medicine Man, and Just Cause were critical and box office failures(although in Marnie’s case, modern criticism has been much more favorable). If Connery lacked the range of his contemporaries—such as Peter O’Toole, Albert Finney, and Michael Caine—he made up for it with sheer bloody enthusiasm. He was a strong, consistent brand, like a 16-year old single malt Scotch whisky (that’s not a typo) that never fails to satisfy. His was a personal brand of machismo; his strength was born in the gut. Sean Connery didn’t need swagger; he had confidence.

Heroes like James Bond could probably never exist. But Sean Connery lived for 90 years. Now, how cool is that?

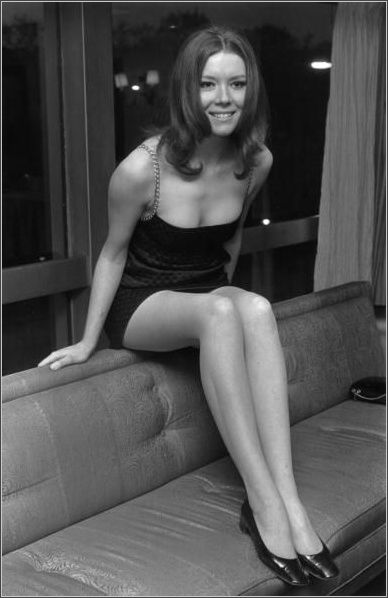

Dame Diana Rigg DBE

July 20, 1938 – September 10, 2020

Thank you for the memories, Dame Diana Rigg. I honor your courage, grace, & wit. You were the muscle behind The Avengers, and your admirers thank the stars for that because Patrick Macnee would have looked awful in catsuits, tracksuits, and fetish wear. You shone as Mrs. Emma Peel & brighten the heavens now.

The Top Six reasons to love Emma Peel (as only Dame Diana could portray her):

6.

Oh, those fashions!

5.

Sultry, seductive, and sophisticated.

4.

Genius in multiple sciences, with particular expertise in chemistry.

3.

How she played with the Queen’s English, from her steady flow of bon mots to her flirtatious innuendoes with Steed.

2.

Skilled martial artist who more often than not is the rescuer rather than the rescued.

And the #1 Reason to Love Emma Peel:

She took no shit—from anyone—and looked damn fine doing it!

“Who’s next?”

All in a day’s work for Mrs. Peel!

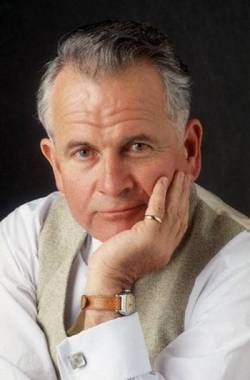

Sir Ian Holm CBE

September 12, 1931 – June 19, 2020

Versatile English actor Ian Holm commanded both the stage and screen in roles ranging from Shakespeare to deepest space. His diverse, exemplary body of work was a feast to be greedily devoured.

He became a personal favorite through his ability to deliver robust, nuanced performances in a number of character roles. He was outstanding in period dramas such as Mary, Queen of Scots; Young Winston; Robin and Marion; Jesus of Nazareth; The Madness of King George; and The Aviator. His performance as the dispassionate robot Ash in Aliens served to cement his appeal as an actor to me. Roles in many other notable genre films—Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein, The Fifth Element, Naked Lunch, and two films each in The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit franchises—would follow.

A trained Shakespearean actor and member of the Royal Shakespeare Company, Holm captivated audiences in choice roles in some of the Bard’s greatest works: Troilus in Troilus and Cressida; Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream; Fluellen in Henry V; and Polonius in Hamlet. His titular performance in a 1998 production of King Lear earned him a coveted Olivier Award.

The 1981 film Chariots of Fire presented him in what was likely his most successful role—that of demanding US Olympics running coach Sam Mussabini. For this performance he won BAFTA and Cannes Film Festival awards for Best Supporting Actor; he was nominated for an Academy Award in this same category.

However, I best remember Ian Holm for his portrayal of Captain Philippe D’Arnot, Tarzan’s fiercely loyal friend and tutor, in the 1984 film Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes. If Christopher Lambert’s feral hero was the heart of the film, D’Arnot was the emotional soul, anchoring the fantastic elements of the Tarzan mythos to a realistic 19th Century Africa and England. His warm, earnest performance garnered him a BAFTA nomination. I mark this role as the finest performance of his career.

I will also freely admit to having an Ian Holm guilty pleasure: His turn as a short-fused (no pun intended), but weirdly charming Napoleon in Time Bandits. This rare—and somewhat dark—excursion into comedy led me to question why Holm did not do more of this type of role during his distinguished career.

Ian Holm leaves us with an envious body of work that will entertain and nourish his fans and generations of future cinephiles. Farewell, Mr. Holm—May the Map of the Universe unfold and the Supreme Being guide you home.

When giants fall, our grief in their passing should not cause us to lose sight of the profound footprints they left behind.

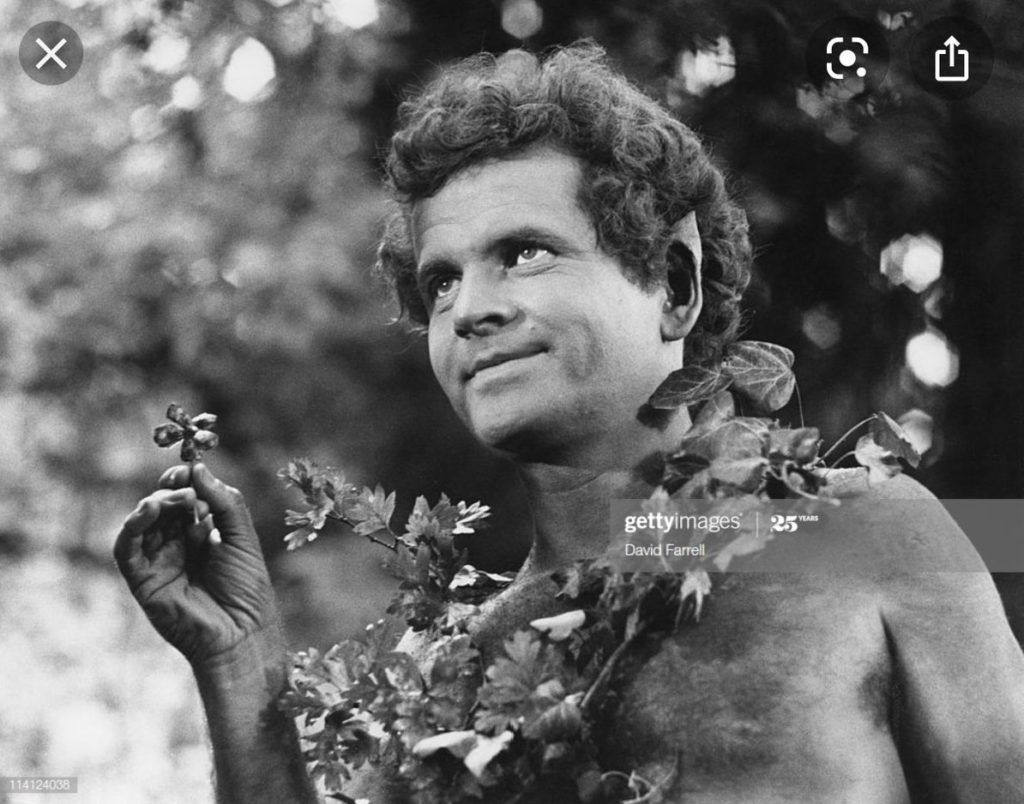

Puck

A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1968)

The queen’s advisor David Riccio

Mary, Queen of Scots (1971)

Lenny in The Homecoming (1973)

Prince John

Robin and Marion (1976)

The robot Ash in Alien (1979)

Coach Sam Mussabini

Chariots of Fire (1981)

Napoleon in Time Bandits (1981)

Capt. D’Arnot

Greystoke (1984)

Attorney Mitchell Stephens

The Sweet Hereafter (1997)

Father Vito Cornelius

The Fifth Element (1997)

King Lear (1998)

Bilbo Baggins

The Lord of the Rings / The Hobbit

Max von Sydow

April 10, 1929 – March 8, 2020

If bleak and disturbing Swedish cinema (Det Svenska Tungsinnet aka The Swedish Gloom) is your bag, you can’t go wrong with the early films of Max von Sydow (born Carl Adolph von Sydow). These films were punctuated by murder, rape, and insanity—and that’s just in the first 20 minutes! Throw in suicide, war, poverty, disease, moral failure, sexual frustration, sexual coercion, shame, self-loathing, self-destruction, religious intolerance, and the struggle to reconcile human tragedy with the (alleged) existence of God, and you’ve got the formula for an evening of cinematic flagellation.

If not for von Sydow’s gripping screen presence and commanding voice, films such as The Seventh Seal, The Virgin Spring, Through a Glass Darkly, and The Emigrants would have been unbearable for anyone other then stoic, brooding Swedes (possibly Norwegians and Danes as well). He has my respect for his ability to inject raw anguish or turmoil into his characters, humanizing them rather than portraying them as soulless or unhinged monsters. Moreover, he gets extra credit for remaining sane after performing in these hellish cinematic nightmares (yes, I am not a Bergman fan) and not hanging himself from the rafters of a shack in a remote fishing village on the banks of the Indalsälven River.

That said, that will be all that will be said here about that phase of von Sydow’s career. It is included because no tribute to the actor can be complete without even a passing reference to his Swedish films. This tribute has a focus on a different horizon.

A star of stage, screen, and television, Max von Sydow enjoyed a career that spanned nearly 70 years. Due to his talent, austere features, and grave, penetrating voice, he was a respected, commanding presence in—and much in demand for—dozens of Swedish, French, Italian, English, and American film productions.

His film legacy alone includes acclaim (The Seventh Seal, The Emigrants, Flight of the Eagle, Hannah and Her Sisters, Pelle the Conqueror), controversy (The Exorcist, Illustrious Corpses) and disaster (The Greatest Story Ever Told, Brass Target, Until the End of the World) alike. He performed in films that are forgotten gems (Three Days of the Condor, Death Watch, Duet for One) and those best left forgotten (The Quiller Memorandum, A Kiss Before Dying, Druids). He also featured in a slew of genre films (Conan the Barbarian, Dune, Judge Dredd, Minority Report); he was a pussy-stroking villain in Never Say Never Again and an ally to Luke Skywalker in Star Wars: The Force Awakens. Two of his films, Flash Gordon and Strange Brew, have achieved cult status.

Von Sydow reaped several significant honors during his lifetime: The Royal Foundation of Sweden’s Cultural Award, and a Commandeur des Arts des Lettres and Chavalier de la Légion d’honneur from France. For his role in Flight of the Eagle he won the Best Actor award at the 1982 Venice Film Festival. In addition, he received a Golden Globe nomination for Best Supporting Actor for Hawaii (1966), and Oscar nominations for Pelle the Conqueror (1987) and Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close (2011).

Clearly, von Sydow could peel the words from the pages of any screenplay and weave them into a wardrobe he could inhabit to create the multiple heroes and villains, monarchs, messiahs, and mere mortals he portrayed on screen—all with the ease of a mythological being reshaping its form. Of all his diverse roles, one has particularly captivated me and left an indelible impression: Major Karl von Steiner in Victory (or Escape to Victory, if you prefer), a sports drama set in WWII. I grant that this choice is most likely not to be favored—or even understood—by you. But I have no concern for the musings of fleshlings.

Since Victory’s release, sports fans have overlooked the veteran actor’s performance—gravitating instead toward Brazilian superstar footballer Pelé—and von Sydow’s elitist fans ignore the film entirely. Having portrayed a medieval knight, a fanatical minister, a hardscrabble immigrant, a beleaguered priest, and even Jesus Christ, von Sydow’s role of a Nazi in a summer action movie could be perceived as a career misfire. However, such a conclusion would be a mistake.

So why is this role in this film special? Short answer: because von Sydow is daunting and elegant. He demands your attention and, despite his character being a Nazi, earns not your contempt but your respect! He wipes his feet on the trope of the Nazi villain. No small accomplishments, to be sure. His is a performance fueled by ghosts of the Shakespearean stage. Every line of dialog is a gift. Each expression is a revelation.

Click below for an in-depth discussion of Max von Sydow in Victory.

In lesser hands, von Steiner could have been a caricature of a Nazi villain: the haughty officer who underestimates his opponent, perhaps;the overly-solicitous or brilliantly manipulative negotiator;or even the hostile or psychotic nationalist. But with von Sydow in control, the major rises above such clichés so as to avoid being nothing more than a necessary, but inert, plot device. He is a formidable adversary: intelligent, shrewd, cultured, yet unduly conflicted by his circumstances.

Von Sydow touched the core of Major von Steiner and brought his essential qualities before the cameras, realizing the major through infusions of camaraderie, courage, and honor. His portrayal is of a loyal, if perhaps reluctant Nazi who seems to prize being a gentleman over his status as an officer. He reveals a conflict between duty to country and the responsibility of conscience. Von Sydow’s Major von Steiner is a worldly man who understands that those who are labeled as his enemies are only enemies in the context of the madness of war.

As is typical with von Sydow, his effortless deployment of his commanding voice, expressive features, and regal bearing complimented his performance. Through these features, he delivered a fresh, authentic character to the drama.

Major von Steiner may have been conceived by a screenwriter, but Max von Sydow issued him life and made him vibrant. Von Sydow adds a gravitas to Victory that improves it as a war film and elevates it above a mere sports film. He gives a rich performance that is immediately captivating and, ultimately, unforgettable.

That said, remember that Victory is just a single slice from von Sydow’s storied career—a small role in a largely unheralded film. Now imagine his brilliance in any of his other better known and classic performances. If that is too daunting a task for you, watch him work his craft in a more accessible role, such as Ming the Merciless in Flash Gordon; the entrenched, morally ambiguous assassin in Three Days of the Condor; Brewmeister Smith in Strange Brew; or a reclusive painter in Woody Allen’s Hannah and Her Sisters.

As an actor, Max von Sydow was more than Antonius Block. He was more than Karl Oskar, or Father Merrin, or even Jesus Christ. He was an incredible talent who submerged himself in diverse characters to deliver authentic, moving performances. Even his most ardent fans need to embrace this. Those unfamiliar with his work should do their due diligence and discover von Sydow for themselves.

Farewell, Max von Sydow. Although time has taken you from us, your body of work remains behind for generations of film lovers to absorb and enjoy. Even those dark, dispiriting, disturbing Swedish movies. Vila i frid.